STS-75 Fact Sheet

By Cliff Lethbridge

STS-75 — Columbia

75th Space Shuttle Mission

19th Flight of Columbia

Crew:

Andrew M. Allen, Commander

Scott J. Horowitz, Pilot

Franklin R. Chang-Diaz, Payload Commander

Jeffrey A. Hoffman, Mission Specialist

Maurizio Cheli, Mission Specialist

Claude Nicollier, Mission Specialist

Umberto Guidoni, Payload Specialist

Orbiter Preparations:

Tow to Orbiter Processing Facility – November 5, 1995

Rollover to Vehicle Assembly Building – January 23, 1996

Rollout to Launch Pad 39B – January 29, 1996

Launch:

February 22, 1996 – 3:18:00 p.m. EST. Launch occurred as scheduled with no delays.

During ascent, the crew reported that the left main engine chamber pressure tape meter was reading only 40% thrust instead of 104% prior to main engine throttle-down.

If the actual thrust had been 40%, NASA managers could have ordered an emergency abort landing.

However, mission controllers in Houston reported that their telemetry indicated nominal main engine performance. With an apparent failure of an indicator only, Columbia reached orbit flawlessly.

Landing:

March 9, 1996 – 8:58:21 a.m. EST at Runway 33, Kennedy Space Center. Rollout distance was 8,459 feet. Rollout time was 64 seconds. Mission duration was 15 days, 17 hours, 40 minutes, 21 seconds. Landing occurred during the 252nd orbit. The mission was extended one day due to poor weather at the Kennedy Space Center.

Mission Summary:

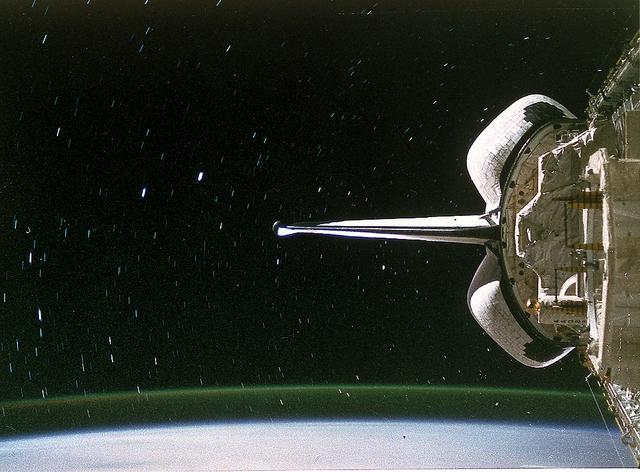

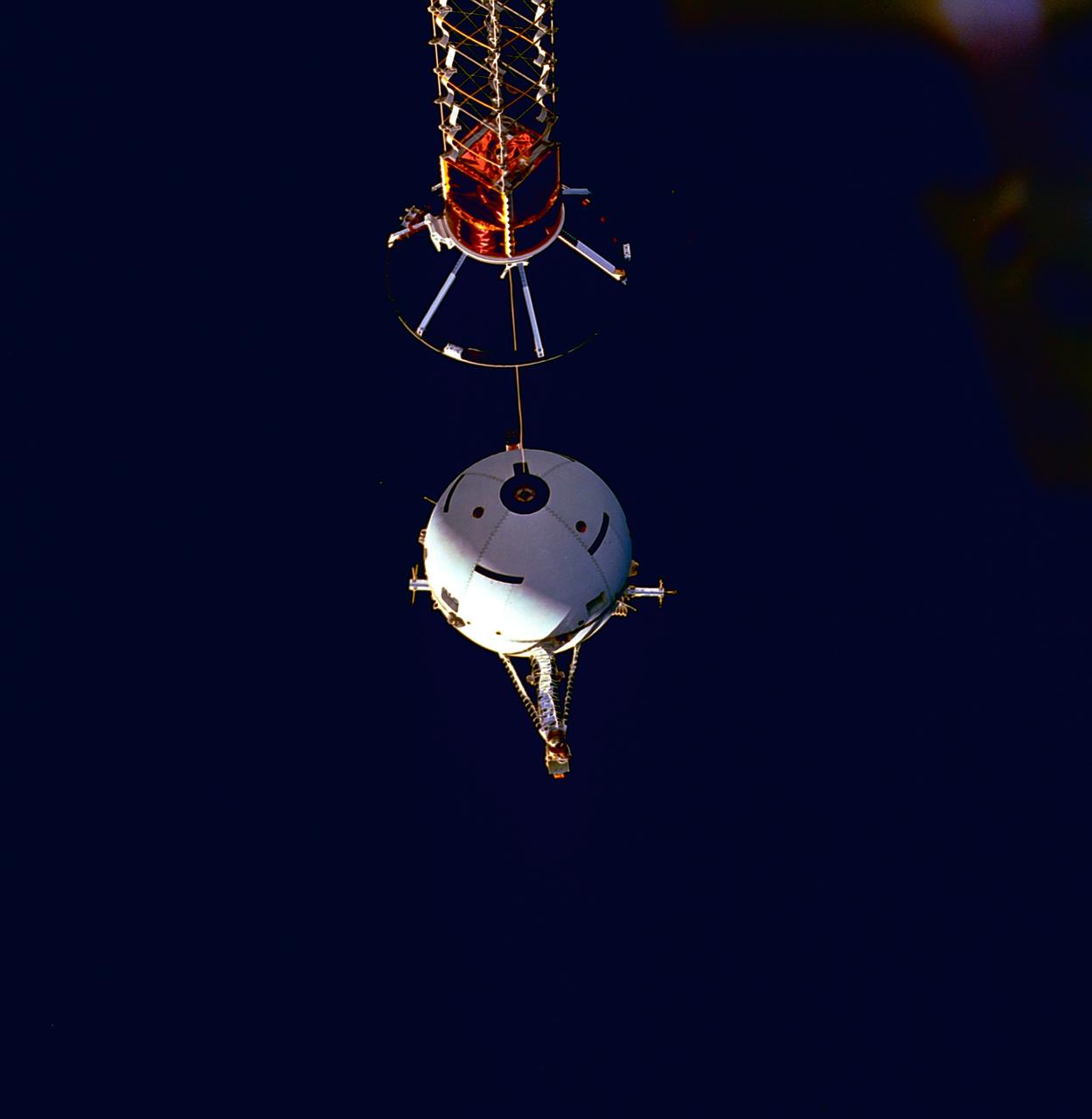

Primary payloads were the U.S./Italian Tethered Satellite System (TSS-1R) satellite and the U.S. Microgravity Payload-3 (USMP-3) scientific package housed in the Shuttle’s payload bay.

The TSS satellite, flown for the second time, had been unsuccessfully deployed during STS-46 in June, 1992 due to a jammed tether. TSS deployment during STS-75 was delayed one day to allow troubleshooting of onboard TSS computers.

The satellite, attached to Columbia by a reeled tether, was designed primarily to collect electricity from the earth’s ionosphere. A total of 12 investigations were incorporated into the spacecraft.

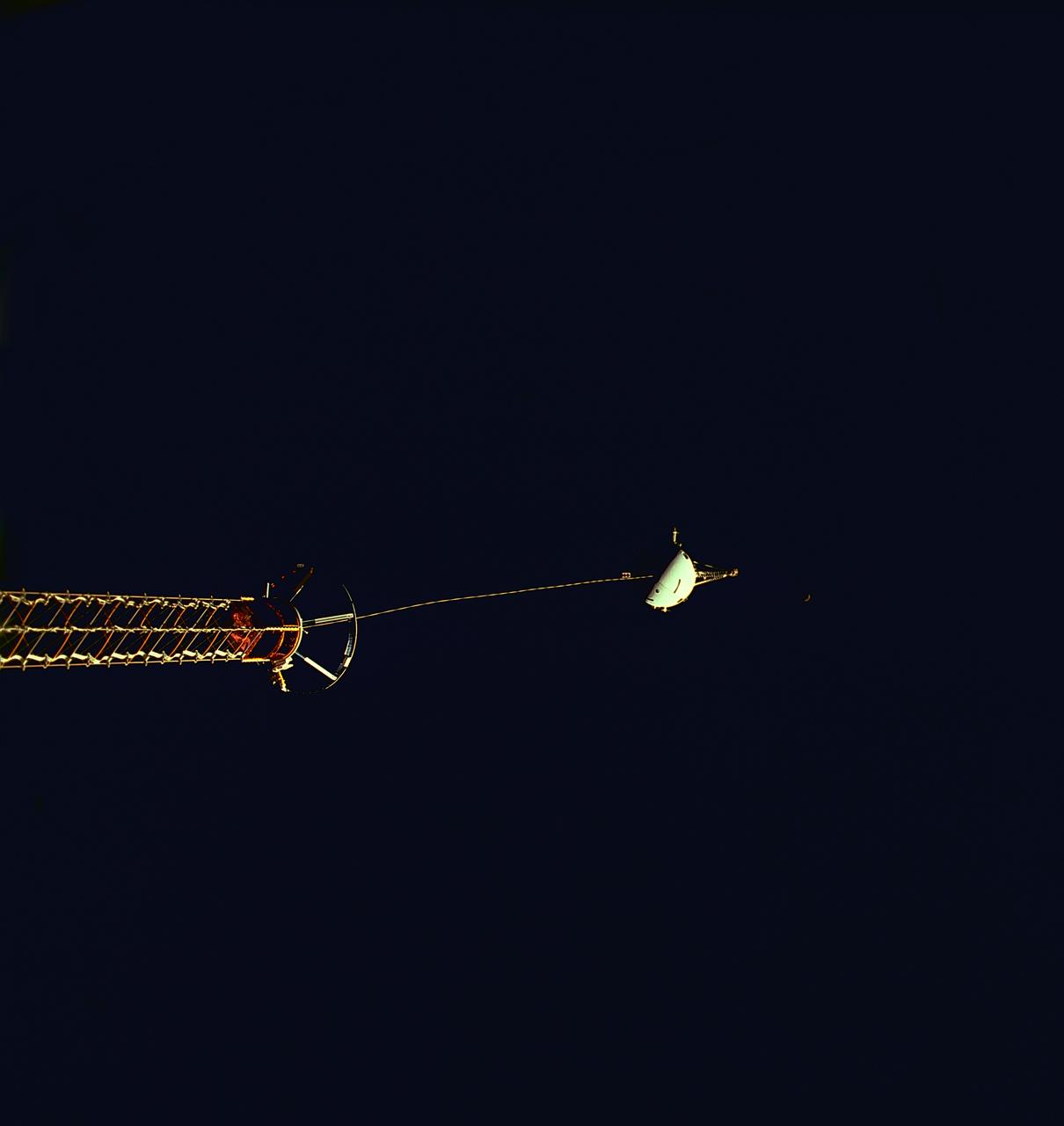

TSS was unreeled to a distance just short of the planned 12.8 miles from Columbia when the tether snapped unexpectedly. The satellite sped away from Columbia, followed by its long tether. There was never any danger to the crew.

NASA decided not to attempt a retrieval of TSS, due to the unpredictable nature of a free-floating 12.8 mile-long tether which might damage the Shuttle. However, despite the tether break, TSS yielded valuable data.

While still tethered to Columbia, TSS generated electric voltages as high as 3,500 volts – nearly three times more than anticipated. A study was also made concerning the interaction of TSS thrusters and the ionosphere, and observation was made of an ionized shock wave that was created around TSS as it moved.

First-time data was also obtained concerning the plasma wakes created by an object as it moves through the ionosphere. After the tether break, TSS was still able to provide limited data via radio transmission prior to burning up as it re-entered the earth’s atmosphere.

USMP-3 experiments included the Advanced Automated Directional Solidification Furnace (AADSF) crystal growth facility, Critical Fluid Light Scattering Experiment (Zeno) to study the element Xenon and Isothermic Dendritic Growth Experiment (IDGE) to grow dendrite crystals.

The fourth USMP-3 experiment was Materials for the Study of Interesting Phenomena of Solidification on Earth and in Orbit (MEPHISTO) to study how metals solidify in microgravity using a furnace.

Space Acceleration Measurement Systems (SAMS) and Orbital Acceleration Research Environment (OARE) were again flown to study the Shuttle’s on-orbit environment.

The crew also worked using the Middeck Glovebox Facility (MGBX) featuring three experiments in combustion. Also flown was the Commercial Protein Crystal Growth-9 (CPCG-9) experiment.

SELECTED NASA PHOTOS FROM STS-75