LAUNCH COMPLEX 39 FACT SHEET

By Cliff Lethbridge

Aerial View Of Launch Complex 39 Circa 2018

LAUNCH COMPLEX 39

Configuration: Remote Firing Room, Two Launch Pads

LAUNCH PAD 39A

Current Status: Active

First Launch: November 9, 1967

Final Launch: Active

Number of Launches: Active

Vehicles Launched: Saturn V Apollo, Saturn V Skylab, Space Shuttle Columbia, Space Shuttle Challenger, Space Shuttle Discovery, Space Shuttle Atlantis, Space Shuttle Endeavour, Falcon 9, Falcon Heavy

Aerial View Of Launch Pad 39A Circa 2018

LAUNCH PAD 39B

Current Status: Active

First Launch: May 18, 1969

Final Launch: Active

Number of Launches: Active

Vehicles Launched: Saturn V Apollo, Saturn IB, Space Shuttle Challenger, Space Shuttle Discovery, Space Shuttle Atlantis, Space Shuttle Columbia, Space Shuttle Endeavour, Ares I-X

Aerial View Of Launch Pad 39B Circa 2018

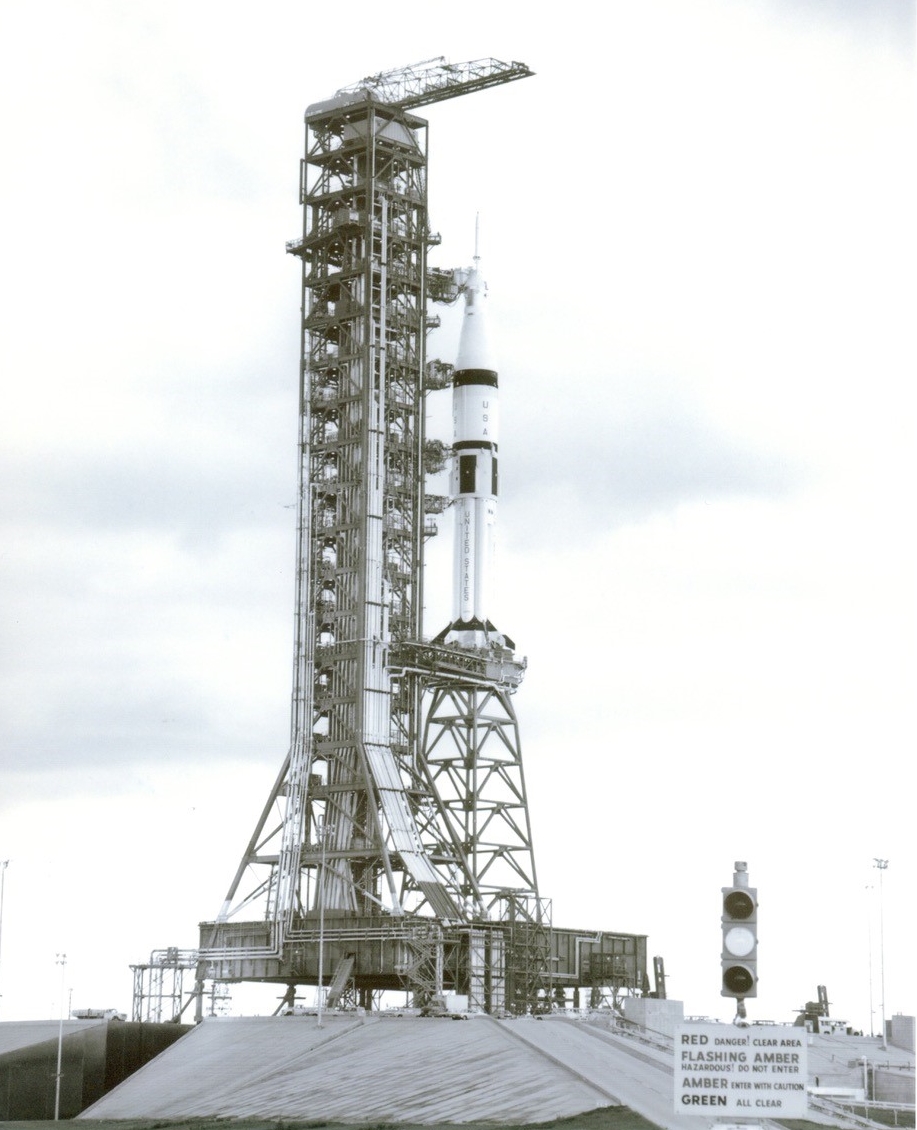

Launch Complex 39 was constructed in support of Saturn V rocket preparations and launches. A brief history of the complex is included below. The site remained largely intact through the Skylab and ASTP programs, for which a large metal pedestal was erected at Launch Pad 39B. Nicknamed the “milkstool”, the pedestal allowed the Saturn IB launch vehicle to meet existing Saturn V launch tower hardware, which dwarfed the much smaller Saturn IB.

Launch Complex 39 was renovated for the Space Shuttle program, with most of the modifications located at Launch Pads 39A and 39B. A fixed service structure was built on both launch pads, which wrapped around the Space Shuttle during launch preparations and rolled back on hinges as the launch neared. Upon the conclusion of the Space Shuttle program, much of the vehicle-specific Space Shuttle hardware at the launch pads has been destroyed.

Launch Pad 39A was renovated for SpaceX Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches. Launch Pad 39B is undergoing renovation for the NASA Space Launch System (SLS) program. Dwarfed by the massive Launch Pad 39B, Launch Pad 39C was recently constructed in the southeast perimeter of the pad area. Called the Small Class Vehicle Launch Pad, Launch Pad 39C is intended for use by companies launching small rockets.

Aerial View Of Launch Pad 39C Circa 2018

Excerpt From: History Of Cape Canaveral

Construction Of Vehicle Assembly Building Circa 1965

Clearly the largest and most famous of all Cape Canaveral launch complexes, Launch Complex 39 on Merritt Island was originally built for the sole purpose of sending men to the Moon and back.

By the late 1950’s, it was clear that geographic Cape Canaveral was running out of room, with launch sites lining the coastline from tip to tail. In April, 1960 the Department of Defense issued a report stating that, “(Cape Canaveral is) substantially saturated with missile launching facilities and test instrumentation.”

This revelation proved problematic for the space program, especially an ambitious effort by NASA to build a vigorous manned spaceflight program. In support of the NASA manned spaceflight activities, it was clear that more land for launch areas was necessary.

Even before NASA embarked on a manned lunar landing program, the space agency planned to dramatically expand its use of large, heavy lift rockets. The first of these was the Saturn I, which was designed in a number of configurations to meet manned and unmanned NASA applications.

Initial NASA forecasts called for as many as 100 launches of Saturn-type rockets per year. Cape Canaveral could host just two Saturn I launch complexes, Launch Complex 34 and Launch Complex 37. The former could accommodate a maximum of four Saturn I launches per year, while Launch Complex 37 could accommodate a maximum of eight Saturn I launches per year.

It was clear that if NASA required 100 Saturn-type launches per year, or even 20 Saturn-type launches per year as mentioned in more conservative forecasts, more land than was available on Cape Canaveral would be needed. NASA also envisioned larger and larger rockets for introduction in the future. These rockets could not be serviced in the relative confines of geographic Cape Canaveral.

By early 1961, NASA developed and refined a mobile launch concept, whereby a central processing area would service multiple launch pads. This would make launch processing more efficient, decrease the time a rocket spent at the launch pad and decrease the amount of land required for each individual launch area.

Initial mobile launch concepts called for a vertical transfer of the rocket from a central assembly area to the launch pad by barge or train. In April, 1961 the NASA Future Launch Systems Office issued a report recommending that the assembly area and transfer method be designed specifically for the rocket being used.

A design for the specific technical criteria for the next Saturn-type launch complex, designated Launch Complex 39, was scheduled to be decided upon not later than January, 1964. A decision was made to design the launch complex to be technically compatible with whatever program NASA would be supporting, even if this proved to be substantially more expensive than existing launch complexes.

At the time, NASA had not decided upon a method of sending men to the Moon and returning them safely to Earth. Hence, the design of a new launch complex would have to wait until a specific program was adopted. There were three basic methods proposed, each of which would require different launch concepts.

The first would employ one huge rocket called Nova, which would send the astronauts on a direct ascent to the Moon. The second called for the launch of multiple Saturn-type rockets followed by an Earth-orbit rendezvous, then a trip to the Moon. The third called for the launch of multiple Saturn-type rockets followed by lunar-orbit rendezvous.

An announcement by President John F. Kennedy on May 25, 1961 that the U.S. would send men to the Moon and return then safely to Earth by the close of the 1960’s forced NASA to settle on one launch method and construct its new launch facilities as soon as possible.

The Nova super booster plan was rejected early, because it could not have been accomplished until after 1970 at the earliest. Either of the two multiple Saturn-type rocket launching methods would be better, but would still require the construction of a large, new launch site.

On June 16, 1961 an ad hoc committee of the NASA Office of Space Flight Programs, headed by William Fleming, recommended that the construction of a new NASA launch site be given a high national priority. The NASA Launch Operations Directorate (LOD) based at Cape Canaveral and the Air Force Missile Test Center (AFMTC) were given the responsibility of agreeing on a launch site.

By July, 1961 the basic technical requirements of the launch site were decided. These requirements included:

Vertical assembly and checkout of the rocket on a mobile launcher umbilical tower housed in an environmentally controlled building,

Transfer of the assembled rocket and mobile launcher to the launch pad for final checkout, fueling and launch,

Control of launch operations from a remote launch control center with two firing rooms, one for checkout and one for launch,

Automated checkout and launch of the rocket.

A railroad type transfer system of the rocket to the launch pad was initially considered most feasible, but transfer by barge or even roadway were also retained as viable options.

As larger variants of the Saturn rocket emerged from the drawing boards, NASA refined the criteria to include more buildings for spacecraft processing and launch control, a launcher/transporter with a pedestal for the rocket and an arming tower to be located midway between the assembly area and the launch pad where solid propellant devices and ordnance would be installed.

Although Merritt Island, located to the north of Cape Canaveral, remained the prime site selection for NASA, a conflict with the Air Force developed. The Air Force wanted to reserve that land to allow expansion of Air Force rocket programs. This forced NASA to review the following possible launch sites:

- Merritt Island

- Man-Made Facilities Offshore Cape Canaveral

- Mayaguana Island, Bahamas

- Cumberland Island, Georgia

- Mainland Site Near Brownsville, Texas

- White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico

- Christmas Island, South Pacific

- South Point, Island Of Hawaii

White Sands was rejected because the site was landlocked. Excessive cost of development ruled out Mayaguana, Christmas Island and Hawaii. Brownsville, Texas was eliminated because rockets would need to fly over populated areas. Cumberland Island was rejected due to unacceptable interference with the Intracoastal Waterway and a lack of infrastructure.

In point of fact, constructing a man-made launch site offshore Cape Canaveral was found to cost only 10% more than constructing a launch site on Merritt Island, but maintenance costs were projected to be astronomical. These prevailing factors left Merritt Island as the only logical choice.

Merritt Island produced just two negative factors, which were the high cost of land acquisition and higher than average cost of utilities. Merritt Island remained a natural choice due to a strong, rocket-based economy, talented work force and existing range infrastructure at Cape Canaveral that would not need to be duplicated.

As a result, NASA requested appropriation for initial land purchases on Merritt Island on September 1, 1961. The first request was for a 200 square mile area immediately north and west of existing launch sites on Cape Canaveral.

On September 21, 1961 the Army Corps of Engineers was requested to begin acquiring the land by purchase or condemnation. Most of the land was purchased with the cooperation of the owners, but as was the case with Cape Canaveral, some land owners exhausted court action prior to leaving or selling.

This gave NASA access to land, but no firm plans for a launch site. In November, 1961 the Saturn C-5 (later renamed Saturn V) was proposed as a launch vehicle considered to be more efficient to support the lunar landing missions. It was not large enough to support a direct ascent to the Moon, but it was large enough to fly all elements on a single rocket for the other lunar landing options.

Development of the Saturn V was approved on December 4, 1961. In January, 1962 the Saturn V was officially selected as the rocket which would be used to support manned flights to the Moon. With the decision in hand, NASA began refining its design of Launch Complex 39 on Merritt Island.

Conflicts with the Air Force continued over use of the range, because NASA sought their own jurisdiction over their own launch activities. The Air Force sought to continue control of the range at Cape Canaveral, with NASA as a tenant. The Air Force viewed Merritt Island as an extension of the range at Cape Canaveral, but NASA wanted their own property rights.

With the issue of the placement of expanded Air Force facilities on Merritt Island also in question, a joint NASA-Air Force team began meeting on February 19, 1962 to iron out the logistical problems. It would take about a year to settle these issues.

Meanwhile, design of Launch Complex 39 took shape quickly. The main technical challenge was the method of transporting the huge Saturn V from the assembly area to the launch pad. Transport by barge was considered unsafe due to wind resistance, and a railway was considered to be too expensive.

NASA settled on a crawler/transporter, based upon the Bucyrus-Erie 2700 metric ton crawler shovel. A crawler roadway bed could be constructed for half the cost of a railway, so Bucyrus-Erie submitted design modifications of their crawler shovel for the purpose of transporting a Saturn V to NASA in March, 1962. The crawler/transporter concept was approved by NASA on June 13, 1962.

Designs for the rocket assembly area, launch control center, launch pads and a sprawling industrial support area also took shape in 1962. The total cost of Launch Complex 39 was estimated at $500 million, with construction time estimated at three years.

Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama was selected to manage construction of the Saturn V rocket, the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas was selected to manage construction of the spacecraft and the Launch Operations Directorate (LOD) at Cape Canaveral was selected to manage overall integration, testing and launch.

On March 7, 1962 NASA announced that Launch Complex 39 would be established as an independent NASA installation. As a result, the Launch Operations Directorate (LOD) was redesignated the Launch Operations Center (LOC). Dr. Kurt Debus was named LOC Director, after having served previously as LOD Director and Director of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency Missile Firing Laboratory on the Cape.

The conflict between the Air Force and NASA over the management of launch facilities on Merritt Island was settled on January 16, 1963 when an agreement was signed by NASA Administrator James Webb and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

The agreement stressed the high national priority of the NASA manned lunar landing effort, and stated, “The Merritt Island Launch Area (MILA) is considered a NASA installation separate and distinct from the Atlantic Missile Range.” NASA was given title and management of its property on Merritt Island.

The Air Force continued to manage the range, with NASA designated a user. NASA agreed to expand its land purchases by 40 square miles to provide enough land for future Air Force expansion. The Air Force decided to construct a huge launch facility for its Titan III rockets on land dredged from the Banana River north of Cape Canaveral. Only a tiny sliver of south Merritt Island was ever required.

In 1963, NASA negotiated land use agreements for submerged lands, and the National Wildlife Service was authorized to administer lands not needed for development. This resulted in the creation of the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge.

The National Wildlife Refuge was authorized to administer leases on citrus groves, fishing camps and operate Playalinda Beach, a long, pristine beach running north from Launch Complex 39. NASA maintained all other aspects of MILA management.

NASA land acquisition totaling about 88,000 acres was completed by February 1, 1964. As was the case on Cape Canaveral, existing buildings, including an abandoned Standard Oil gasoline station, were adapted for other use by NASA.

Dates differ as to exactly when Launch Complex 39 was activated, but there are three key dates to consider, one for each of the three main areas of the launch site.

A topping out ceremony was held atop the Vehicle Assembly Building on April 14, 1965 marking a milestone in the assembly area. Kennedy Space Center Headquarters was formally opened on May 26, 1965 marking a milestone in the industrial area.

And on May 25, 1966 just five years after the famous mandate from President Kennedy, a dummy Saturn V designated Saturn V 500-F was rolled out of the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Pad 39A, marking a milestone in the launch pad area.

A flurry of activity followed, involving two launch pads, Launch Pad 39A to the south and Launch Pad 39B to the north. This activity culminated in the launch of Apollo 11 from Launch Pad 39A on July 16, 1969. Indeed, a new spaceport had sent the first men to the Moon and back.

Falcon Heavy On Launch Pad 39A Circa 2019

Falcon 9 On Launch Pad 39A Circa 2018

Falcon 9 On Launch Pad 39A Circa 2017

Falcon Heavy On Launch Pad 39A Circa 2017

Discovery On Launch Pad 39A Circa 2011

Ares-IX In Vehicle Assembly Building Circa 2009

Ares-IX On Launch Pad 39B Circa 2009

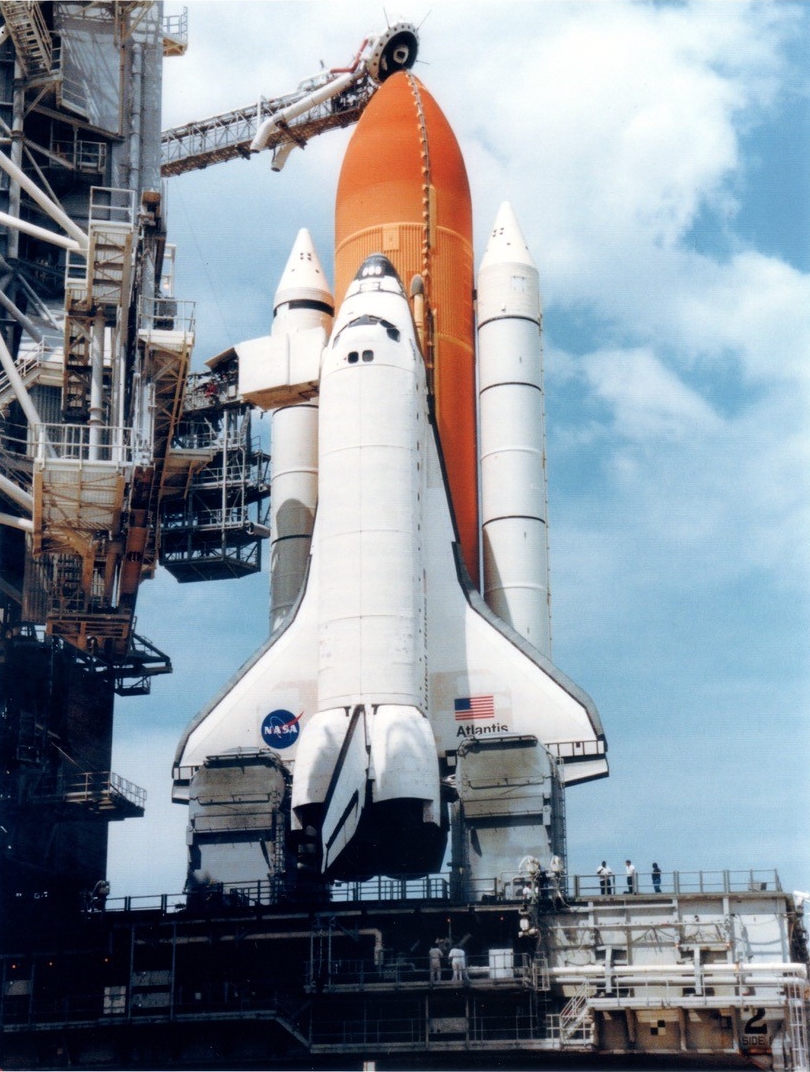

Atlantis On Launch Pad 39B Circa 2000

Discovery Rollout Circa 1995

Columbia On Launch Pad 39A Circa 1982

Launch Pad 39B Milkstool Configuration Circa 1975

Launch Pad 39B Milkstool Configuration Circa 1975

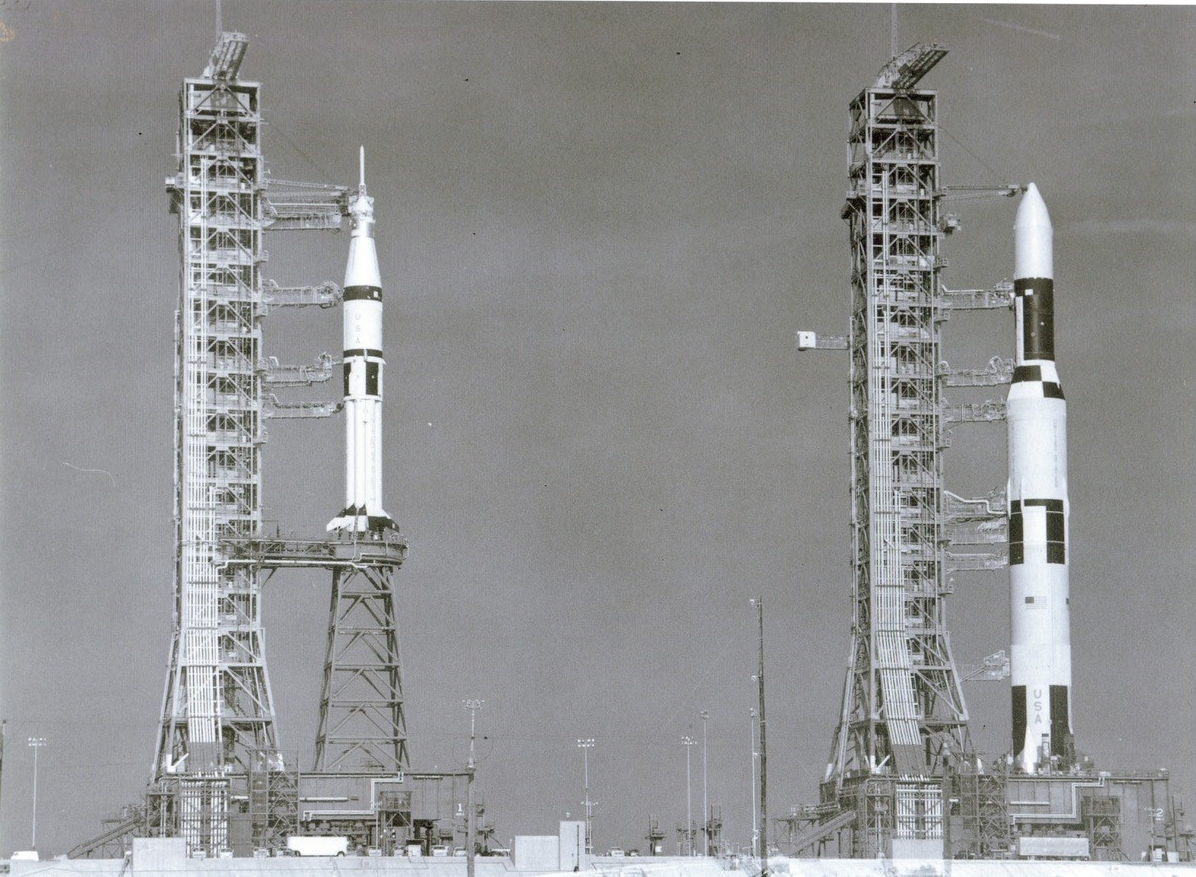

Skylab 2 (Left) And Skylab 1 (Right) Circa 1973

Launch Pad 39B Milkstool Configuration Circa 1973

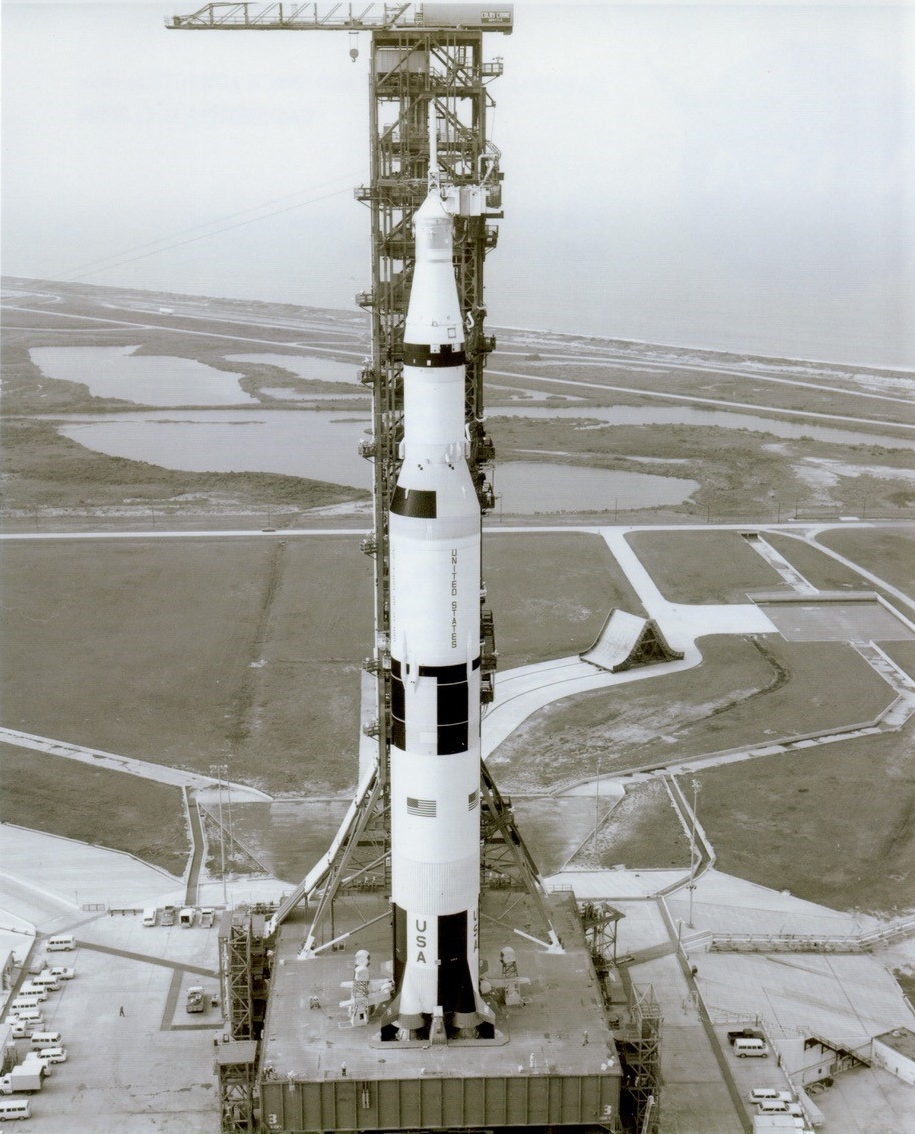

Saturn V On Launch Pad 39A Circa 1972

Saturn V On Launch Pad 39A Circa 1969

Saturn V On Launch Pad 39A Circa 1969

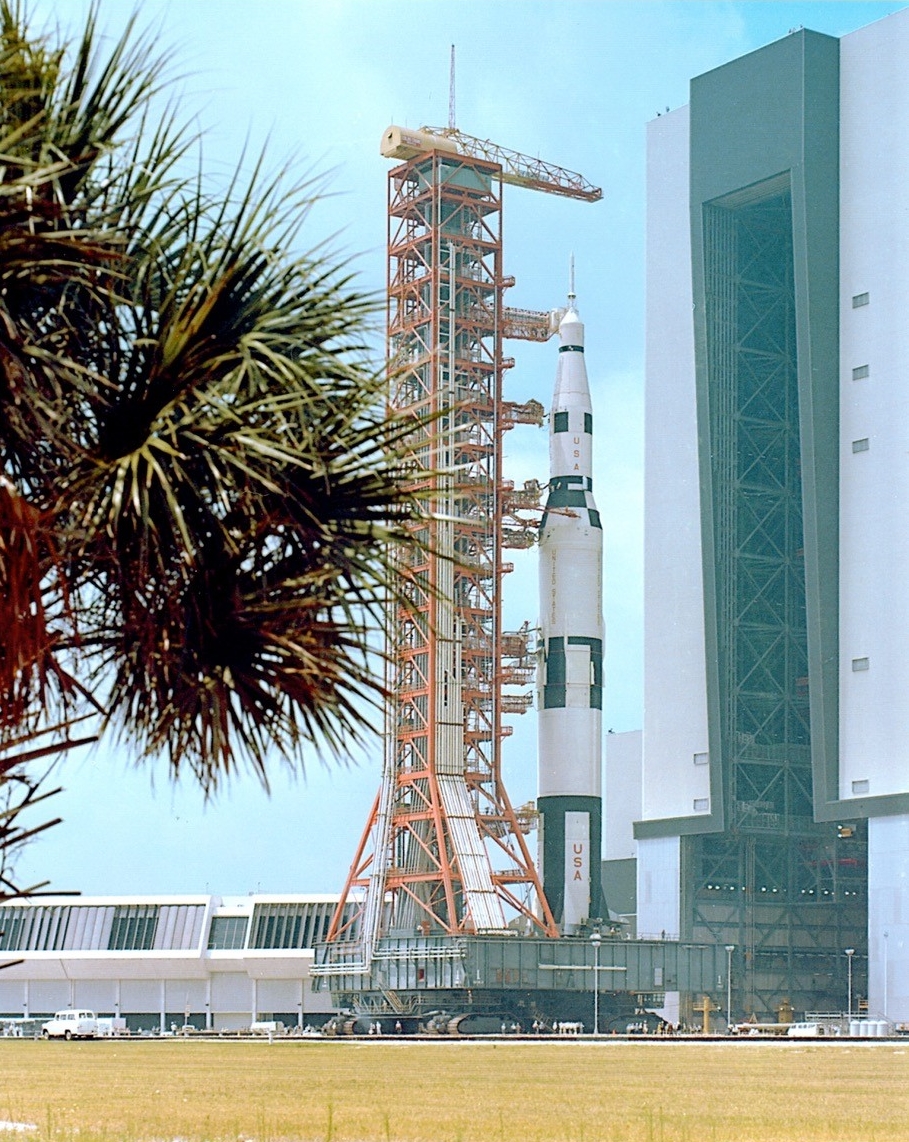

Saturn V Rollout Circa 1966

Saturn V On Launch Pad 39A Circa 1966