LAUNCH COMPLEX 25 FACT SHEET

By Cliff Lethbridge

Aerial View Of Launch Complex 25 Circa 2018

Configuration: Single Blockhouse, Three Flat Launch Pads, One Ship Motion Simulator

LAUNCH PAD 25A

Current Status: Inactive

First Launch: April 18, 1958

Final Launch: March 5, 1965

Number of Launches: 60

Vehicles Launched: Polaris FTV, Polaris A1, Polaris A2, Polaris A3

LAUNCH PAD 25B

Current Status: Inactive

First Launch: August 14, 1959

Final Launch: August 2, 1960

Number of Launches: 8

Vehicles Launched: Polaris A1

LAUNCH PAD 25C

Current Status: Inactive

First Launch: August 16, 1968

Final Launch: January 23, 1979

Number of Launches: 34

Vehicles Launched: Poseidon, Trident I

LAUNCH PAD 25D

Current Status: Inactive

First Launch: September 17, 1969

Final Launch: September 17, 1969

Number of Launches: 1

Vehicles Launched: Poseidon

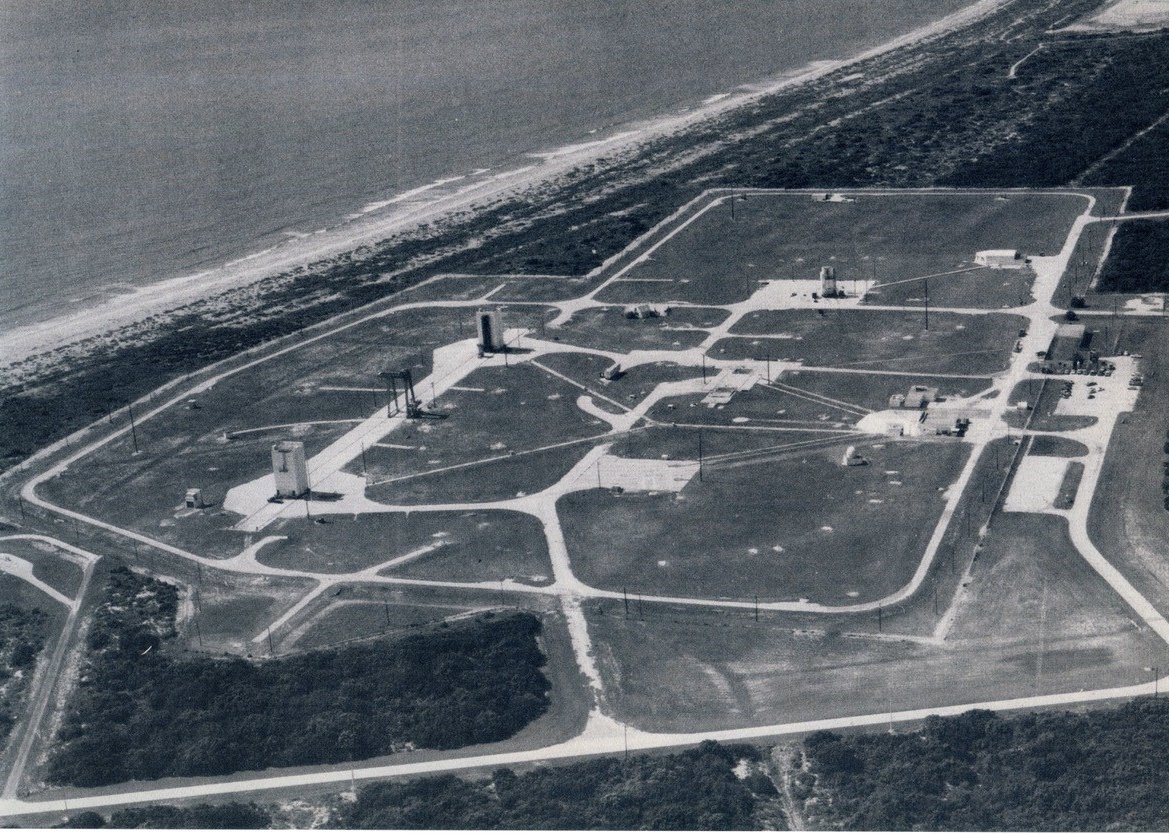

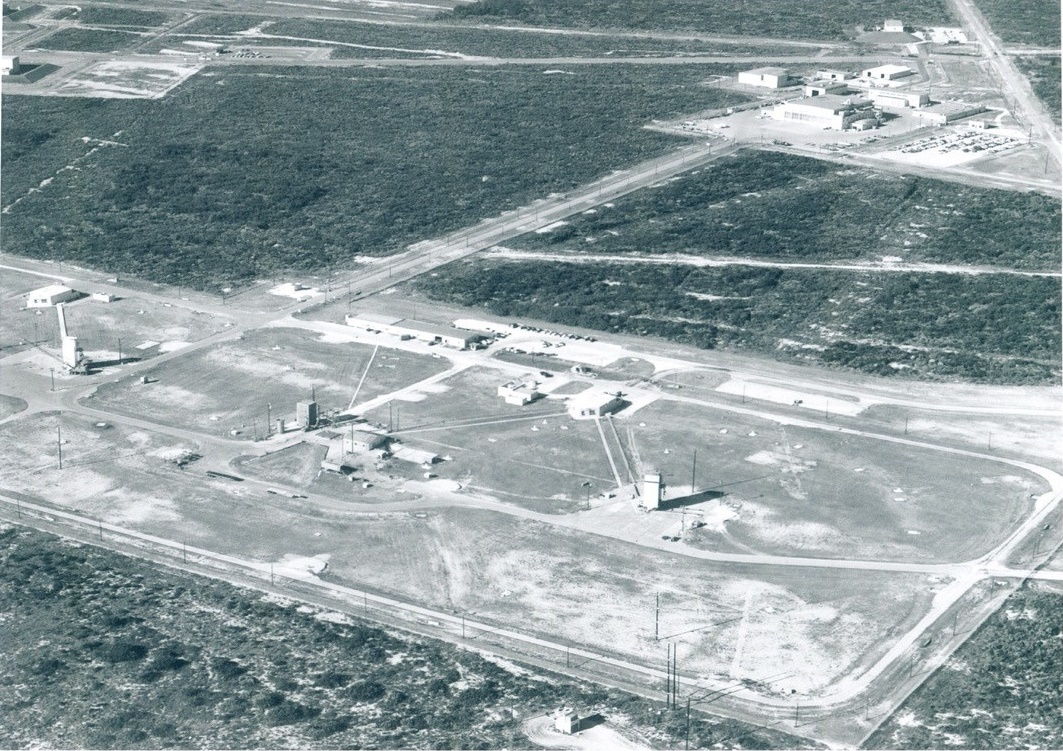

Launch Complex 25 was built in support of Polaris missile testing. The complex was built at a cost of about $4 million. Work on Launch Pad 25A began in early 1957, and the Navy occupied the site on December 18, 1957. Work on Launch Pad 25B began in July, 1957 and the Navy occupied the site on January 30, 1958. The complex originally consisted of a blockhouse and two launch pads, flat pad 25A and ship-motion simulator 25B, not a launch pad in the traditional sense. The site was later modified in support of the Poseidon and later Trident I missile testing programs. Two launch pads were constructed more distant of the blockhouse, and the blockhouse was reinforced on its front, facing newly constructed Launch Pads 25C and 25D. A mobile service tower that could be used on either of these launch pads still exists on Launch Pad 25C.

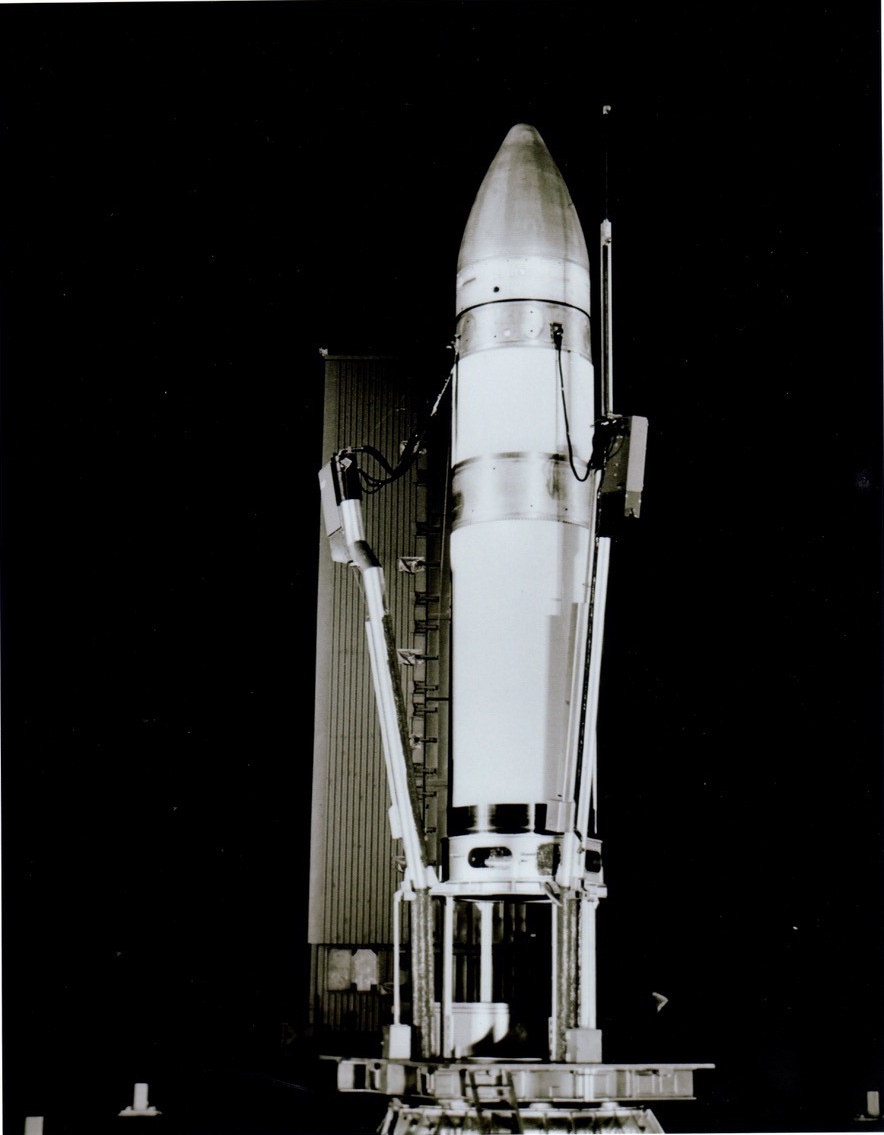

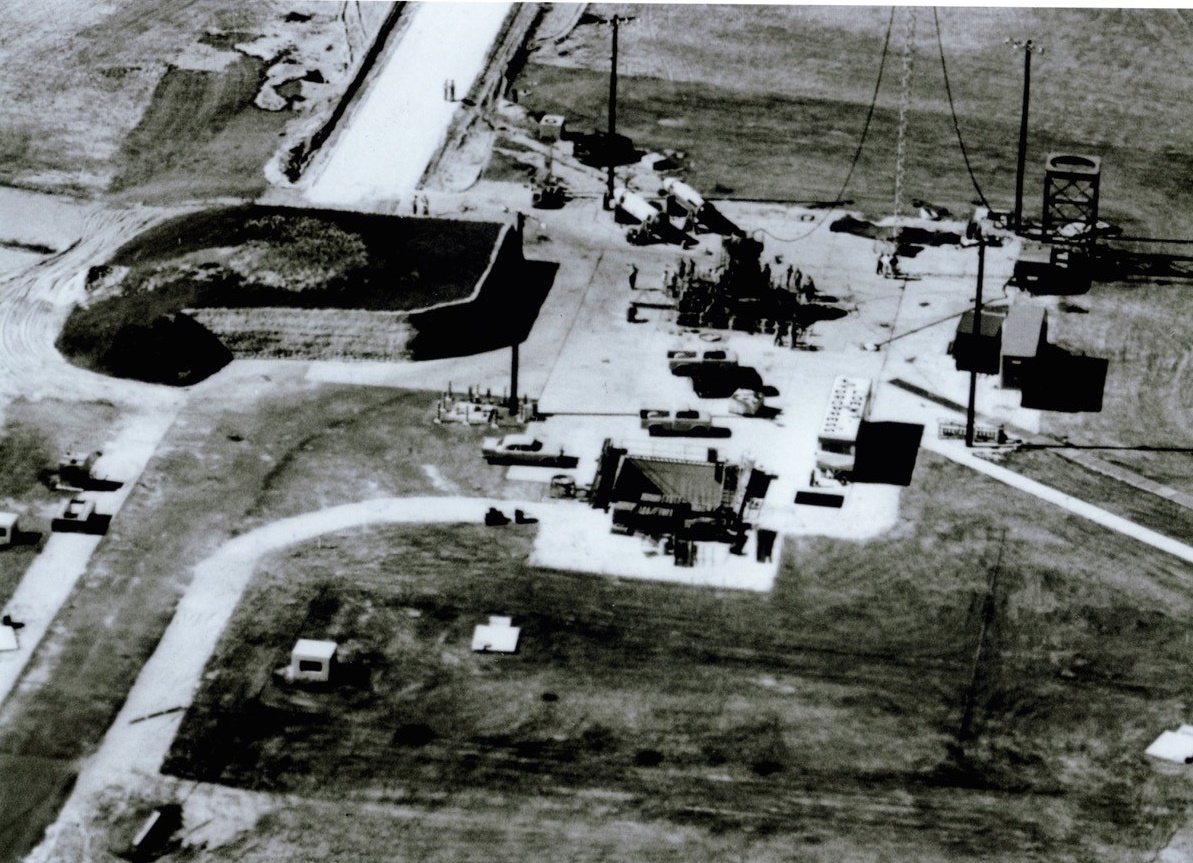

Following retirement of the complex, the blockhouse was converted for office space, with all four launch pads remaining intact. Launch Complex 25 was recently renovated as a missile testing and training facility, although no missile launches will ever occur from the site. One of the most interesting and unique features of Launch Complex 25 was Launch Pad 25B, not in fact a traditional launch pad but an ingenious and sophisticated Ship Motion Simulator (SMS). Nicknamed the “Shaker”, the SMS was designed to simulate the effects of ship motion on a missile before, during and after launch. When the SMS was built and tested in late 1958 the Navy still considered deploying solid-fueled missiles on ships.

Because a ship is more subject to motion than a submerged submarine, engineers needed to be certain that missiles could be safely handled and launched at sea. To do this, the $3 million SMS was installed at Launch Complex 25.The SMS could simulate roll, pitch and heave. These are just three of the six motions a ship is subject to at sea, but only the three motions considered to have an effect on the handling and launching of a missile were incorporated into the SMS.

Designed, built and installed by Loewy-Hydropress Division of Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton Corporation, the 400,000-pound SMS was housed in a 55-foot deep pit measuring 33 feet long by 33 feet wide. A total of 23,000 cubic yards of sand needed to be removed during construction. A seven-foot tall concrete plug was poured at the bottom of the pit. On top of it was placed a square, 47-foot tall box having concrete walls four-feet thick on all four sides. A total of 3,800 cubic yards of concrete was required to complete the structure. Because the average underground water level at the site is just eight feet, an elaborate series of pumps needed to be installed. Adjacent underground equipment rooms and access passageways were also constructed.

The SMS itself consisted of two gimbal-mounted circular rings attached to a series of guides located on the inside walls of the pit. These guides were able to provide a simulation of the vertical heave, or “up and down” motion of a ship. Roll and pitch motion were simulated through the use of four cylinders arranged in opposing pairs. The entire SMS assembly was supported by four hydraulic cylinders. Power was provided by two underground electrical generators, one producing 2,250 horsepower and one producing 700 horsepower. Control of the mechanisms that produced the ship motion was provided by hydraulic pumps operating at 2,000 gallons-per-minute capacity and 3,000 pounds-per-square-inch pressure.

The missile itself was positioned atop the SMS, at more or less ground level. Engineers used three-channel magnetic data tape to record roll, pitch and heave motion at sea, and this relative data was programmed into the SMS. The SMS could simulate roll and pitch to a maximum of plus or minus eight degrees, and heave to a maximum of plus or minus seven feet. Although it was a technical marvel, the SMS was reported to have produced disappointing scientific results. It could only cycle movements in six to 14-second intervals, and so could not accurately simulate the fluid motion of a ship. The SMS did, however, demonstrate that ship motion did not adversely affect the handling or performance of a missile. While the actual SMS hardware has long since been dismantled and removed, the SMS pit and its associated underground equipment rooms remained at Launch Complex 25 for many years. Often completely flooded with water, the SMS pit was well known to be a frequent haunt of Florida alligators. The SMS pit and underground chambers were destroyed and filled in when the launch complex was recently renovated for missile handling and training activities.

Launch Complex 25 Blockhouse Circa 2020

Launch Complex 25 Blockhouse Circa 2020

Mobile Service Tower On Launch Pad 25C Circa 2020

Trident I Launch From Pad 25C Circa 1978

Launch Complexes 25 and 29 Circa 1976

Launch Complex 25 Circa 1976

Poseidon Launch From Pad 25D Circa 1969

Poseidon On Launch Pad 25C Circa 1968

Launch Complexes 25 and 29 Circa 1964

Launch Pad 25A Mobile Tower Circa 1963

Launch Complex 25 Circa 1962

Launch Pad 25B Ship Motion Simulator Circa 1959

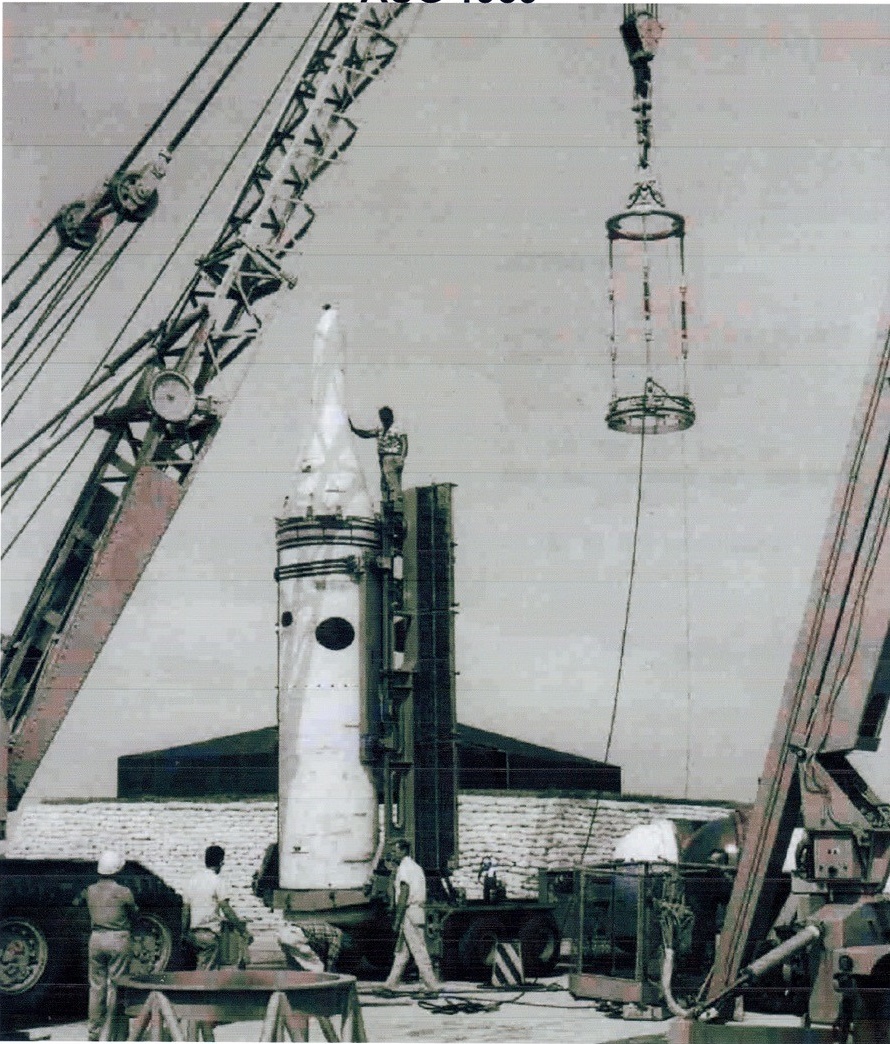

Polaris A1 On Launch Pad 25B Ship Motion Simulator Circa 1959

Polaris A1 On Launch Pad 25A Circa 1958